Riding Alaska’s Dalton Highway: Ice Road Trucking Before the Freeze

We got to be Ice Road Truckers fans at my house, driving the Dalton with every episode. But I never thought, “Wow! I want to do that!” Sometimes, we’d joke about going to Coldfoot, just to cross the Arctic Circle, not that I had any idea what Coldfoot was like, or why you’d want to get that far and just stop. On the other hand, the idea of those 400-plus miles from Fairbanks to Deadhorse and Prudhoe Bay tucked itself away waiting for the right trigger. Like most of my trips, this one just came to me. I went in August when autumn had come to the Dalton and it was frosty in the Arctic.

See “Riding the Dalton Highway: introduction and practicalities” too!

The Dalton Highway – Just My Cup of Labrador Tea!

The Dalton Highway – the Haul Road – is not for people who close their eyes when they get scared, so I looked for the best way to get to Prudhoe Bay without having to drive myself. I booked a three-day, two-night ride with 1st Alaska Outdoor School. There were three of us passengers – me along with seasoned world travelers, caravaners and campers Ulrike and Bernhard from Germany – and Matthew our guide and driver, an old hand at driving the Haul Road who had also worked at the oil fields.

Over four hundred miles each way of two-lane dirt and gravel, potholes, washboard and steep grades. Fifty mph at the fastest. And there’s the special mud. Our driver Matthew told us the state puts calcium chloride on the road in summer to keep down the dust, but when it rains – and we had some drizzle and rain – the calcium chloride turns the road into thick goo. It was like thick dun-colored cake batter and it stuck to everything it touched.

Special Dalton mud

The Dalton starts just under 90 miles north of Fairbanks, following the Alaska Pipeline, which is the road’s reason for existing. The road was built for pipeline construction and then to serve the oil fields. Except for the old gold mining town of Wiseman (population about 14) the couple of places you can sleep started out as man camps during pipeline construction. As you approach the Dalton, you see the sign HEAVY INDUSTRIAL TRAFFIC PROCEED WITH CAUTION. Then, ALL VEHICLES DRIVE WITH LIGHTS ON NEXT 425 MILES. There’s a pullout near the start, a photo op, and a place to mark your real beginning. A beautiful truck pulled in for a stop, all chrome and orange. We talked to the driver’s wife who was along on the trip to keep him company. It’s dangerous, takes all your attention, but gets boring making that 800-plus mile roundtrip day after day. On a steep haul a little farther along, the guardrail was smashed. Matthew said that four days earlier a truck had gone over the side. Driver was OK. Truck totaled. Wrecks happen and don’t always turn out as well for the driver.

A mere 80 or so miles later we crossed the legendary Yukon River. We stopped at the riverbank camp (good to know: flush toilets) and walked down to the river. I put my hand in. Silty and cold. Wide and fast. This is it, the mighty Yukon. Before the bridge that now carries the pipeline and trucks, I understand that truckers drove down the bank on a steep road to a ferry. It doesn’t bear thinking about. Then, mountains, ridge after ridge into the distance. Birch trees. Chilly. We stopped at another pullout and met a man riding the Dalton on his Kawasaki. His riding partner’s bike had broken down – we had seen it going south on a pickup truck earlier. He talked to Ulrike and Bernhard about his German heritage and said he lives and works in Peru’s Amazon jungle. A man who relishes extremes.

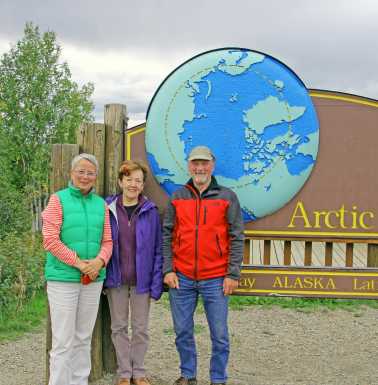

The Arctic Circle

And finally, not yet half way to Deadhorse, the Arctic Circle – the most popular photo op on the Dalton, I expect – and then Coldfoot Camp. Sleeping at Coldfoot is possible. There’s the old man camp. But Ulrike, Bernhard and I spent the night in Wiseman after dinner at Coldfoot Arctic CircleCamp truck stop. Along the way we met a couple from Hong Kong who were in Alaska for a long stay and driving the Dalton themselves. There are so few places to stop that we saw them three times. The last time, we ate together at Coldfoot, feeling like old friends now.

Wiseman. Wiseman (population about 14) had been a gold-mining town around turn of the 20th century. It had stores and a post office that opened in 1909 and closed in 1956. The old post office is half sunken into the ground, which happens when you warm the permafrost. Ulrike, Bernhard and I shared the 2-bedroom Koyukuk cabin. We made tea and shared provisions in the morning before heading back south a few miles for hot food at Coldfoot. There was no food ahead for us for 240 miles if we kept going north.

In the Arctic Circle

On to Deadhorse, Day 2

The Koyukuk River was speeding around tight curves in its shallow bed. Fog hung across the road that morning. Koyukuk, then towering rock formations, the pipeline with golden birch and dark spruce in the middle distance, mountains beyond. We entered “the world’s largest municipality,” the North Slope Borough, and stopped at a pullout at Chandalar Shelf, a long, tortured grade cut into a mountainside, to view the mountains and peer over the steep unguarded drop off. It looked like thousands of feet down to me. Could have been. While we were stopped, a single semi slowly climbed the mountain. We took pictures. Spoiler alert – it was the same truck I rode in the next day!

Atigun Pass. If you watched Ice Road Truckers, you’ll remember the Atigun Pass. A cut through the Brooks Range that reaches nearly 4,800 feet, a muddy (or icy), winding steep grade. The Brooks Range is a northern extension of the Rocky Mountains, the continental divide here in northern Alaska. Peaks reach 7,000 feet. The first sign as we started up into the Pass: “Avalanche area next 5 miles. DO NOT STOP.”

Hauling up the Chandalar Shelf

A trucker I met told me that he thought other places were more dangerous, because the highway department was all over Atigun Pass, but the Pass is dangerous and dramatic. That day in August, there was only a little snow on the mountains but it was cloudy, foggy and windy. Then, when we came down from Atigun Pass, we were on the North Slope. By now I’d lost my sense of time. Driving and driving, wilderness. The different length of day, different quality of sunlight. The Arctic! In what seemed like afternoon, the land had flattened out and we reached the Franklin Bluffs, colorful cliffs of iron-rich rock and soil. All around us there was standing water – water has no place to run off and isn’t absorbed because of permafrost. So it stands in wetlands as far as you can see. It was clear at Franklin Bluffs, but as we came to the coastal plain, cottony fog the color of unbleached muslin surrounded us. And there was road construction under the cover of fog. Floods had washed out parts of the roadway earlier in the season. Visibility was poor. We waited behind a mud-covered SUV carrying a metal canoe for a pilot car to take us through the construction. Dump trucks unloaded gravel. Graders worked it into the new road. Finally, Deadhorse Camp, the end of the highway. It had taken a long time to get here, and then it hadn’t. How to measure?

Welcome to Deadhorse

The Arctic Ocean. We drove through Deadhorse, an amorphous settlement, permanent population in single digits but with a temporary population of several thousand, more or less as needed. It’s an agglomeration of oil field contractors, supply warehouses, extra oil platforms, miles of pipelines. Our rendezvous for the ride to the Arctic Ocean shore was at Deadhorse Camp. We’d be riding across the Prudhoe Bay oil fields and that required a security check. We gathered around tables in the Deadhorse Camp kitchen to have our documents viewed and recorded. Once on the way, pipes, mud, gravel, fog, tangled driftwood logs, 4x4s, wooden crates and other detritus. It was not beautiful. Here, the ocean is technically the Beaufort Sea, a marginal sea of the Arctic Ocean. So let’s just say Arctic Ocean. It was choppy, cold and silty as the Yukon. I showed a picture to a friend with Scottish family. “You could be in Scotland,” he said, “anywhere.” Nothing about it yelled “Arctic,” but I knew I was there.

We had our mid-day meal at an engineering company cafeteria. Was it lunch? Was it lunchtime? Food was healthy, good and plentiful. Someone reminded us that it all came up on a truck. There were strict rules to help keep things healthy. Shed your muddy garments. Wear booties. Always wear vinyl gloves to serve yourself from salad, soup or dessert bars. There were boxes of vinyl gloves all around the cafeteria. We were bright and warm, the building elevated from the ground. It was like a temperate colony on a hostile planet. A man named Michael looked around and said to us, “welcome to all that this is!” We laughed.

After lunch, a quick stop at Deadhorse Camp where Ulrike and I went upstairs to find the rest rooms (more flush toilets). Like at the cafeteria there were absolute rules at the Camp. Absolute. Park your muddy boots and wear booties. The entry ways were a mess with coats, boots and mud on rubber floor runners, but upstairs where there were the sleeping rooms and toilets, it was pristine. The rules worked. We also shopped at the Prudhoe Bay General Store but didn’t buy. This is the only place in Deadhorse to get necessities, clothing, household goods, greeting cards, souvenirs – a real mélange. Then we headed back south. You’ve been there and then you leave, just like that. There’s nothing for a tourist to do. We left Deadhorse at 7 PM. It seemed like afternoon.

Back on the road, the fog had become denser, the wait for the pilot car longer. It was 35 degrees and windy. The person who held the stop sign in front of the traffic was dressed in an unbendable thickness of clothes, bunny boots and a yellow safety costume on top. While we waited we tried to guess the person’s gender. I argued that it was clearly a woman. So our driver Matthew got out, had a smoke, and chatted with the person, who turned out to be a guy from Nome who wants to do this a couple more years and then go to Belize. And as we left the coastal plain, the sky cleared with broken clouds. Brown, copper, cerulean, gray; fireweed and shrubs. Naked mountains deep rose gold in the sunset. Many miles still to go back to Wiseman for our second night. Somewhere along the way, Matthew said he thought he could detect aurora by the glow in the clouds. We found out the next day he was right. We got to Wiseman around 2 AM.

The Day I Rode in a Truck – My Kenworth Ride from Coldfoot to Beaver Slide, Day 3

I’d intended never to mention Ice Road Truckers because that’s exactly what a tourist would do. But I couldn’t keep quiet. I knew the names of the toughest stretches of road and waited for each to come up on our trip. I felt quite expert. We stopped at Coldfoot for breakfast (where else?) our third morning and Matthew asked if I’d like to meet a trucker who drives the ice road (and the mud, dust and everything else road). That was cool. And while we chatted with a bow hunter out for caribou (it being season opener), the trucker, Scotty, asked me if I’d like a ride in the truck. What do you think? Of course! And that’s how I got my ride to Beaver Slide, after which we met up with my group at a pullout. We talked about hunting in Alaska, the climate, the road, fires, accidents. The Arctic Circle. Scotty said he didn’t want to burst anyone’s bubble, but the Arctic Circle is at Connection Rock, not the sign. But there’s a better view from the sign, he added. Riding some of the deep dips along the roller coaster section of the Dalton was somewhere between exhilarating and terrifying.

The truck ride ends

Trucks accelerate going down for momentum to get up the other side. At Beaver Slide I felt like, as I looked down, the road was so steep that I couldn’t see the bottom of the hill. “What happens if you don’t get up the other side?” I asked. “Then you’re stuck down there like a rat!” It’ll block traffic and you’ll need a tow, I’d add from something besides an ordinary tow truck.

As for life on the road, Scotty said, our lives can depend on each other out here. There are some real SOBs but most everybody is fine. I asked whether the TV series was realistic. Yes, but sometimes it’s more “real” here than they could show, he said. He thought the competition thing on the show was just intended to keep up viewer excitement, and they didn’t focus enough on the drivers. Thinking about it, watching the series, I did get to know a little about a few drivers, but he was right. It’s a dangerous, beautiful, boring, exciting and lonely lifestyle. We even talked about arranging for me to ride the Dalton in winter. I haven’t pursued that. Maybe I do better on mud than ice.

Trip date: August 2015